The News You Need To Know | April 2017

What’s an investor to do?

By J. William G. Chettle, VP, Loring Ward

In the 1967 movie, The Graduate, the young college graduate is advised that the future is about one word: “plastics.” The advice was a deliberately absurd laugh line, but in today’s era of unprecedented technical and societal change, we hear similar advice delivered with perfect seriousness. Self-driving cars will change the world! We are on the cusp of revolutions in biotech, renewable energy, robotics, genetics, etc. Heck, we might even get flying cars and jet packs one day soon.

These great changes could very well revolutionize society, but things rarely work out quite as predicted — and even when they happen exactly as planned, trying to invest in the future is still a very risky thing to do.

Some investors believe they will make a fortune if they can only identify the companies that will create the revolutionary products and services of tomorrow. Others believe that established industry leaders such as Apple, Facebook or Amazon will continue to grow, innovate and dominate their competitors and thereby reward investors with strong returns.

If only investing were so easy.

To demonstrate some of the perils of investing in the future, let’s consider a groundbreaking and prescient Time Magazine article published in 1965, “The Computer in Society,” which detailed the ways computers were changing the world.

Time noted that IBM was then the leading global computer company, with 74% of the U.S. computer market, “a dominance that leads some to refer to the industry as ‘IBM and the Seven Dwarfs.’ The dwarfs, small only by comparison with giant IBM: Sperry Rand, RCA, Control Data, General Electric, NCR, Burroughs, Honeywell.”

But Time’s reporting was already behind the times, neglecting to mention a computer firm that would transform computing and become one of the 20 largest companies in America. Founded in a garage in Menlo Park, CA, in 1947, Hewlett Packard (HP) would enter the computer market in 1966 with the HP 2116A minicomputer — one of the first portable and “plug and play” computers.

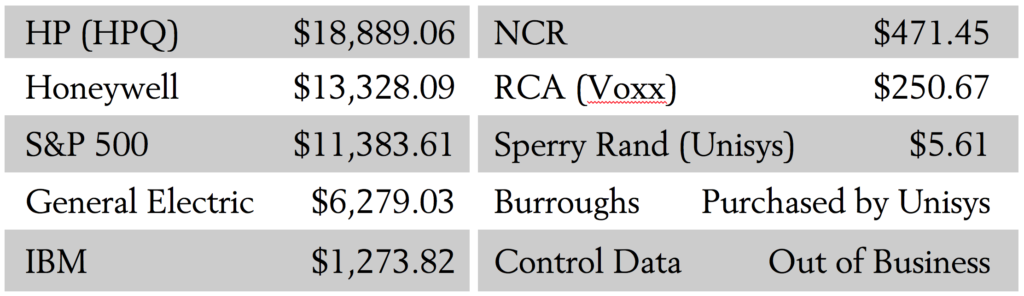

As a thought experiment, let’s say that you were convinced by the Time article that computers would change the world and called your stockbroker and invested $100 in IBM as well as in each of the Seven Dwarfs at the beginning of 1966. You’ve also heard something about HP, so you invest $100 in their stock, as well as $100 in the S&P 500 for a little more diversification. If you’d stayed invested for the next 50+ years through 2016, here’s how your investment in the future would have done…

Growth of $100 Investment (1966 – 2016)

Source: S&P 500: DFA Returns 2.0, IBM and GE: Morningstar Direct;

HPQ, Unisys, Voxx, NCR and Honeywell: Yahoo Finance

Looks like investing in the future was a pretty good idea, until you consider the top-performing stock of that same period — a company that makes a heavily regulated, low-tech product. If you had invested $100 in Phillip Morris/Altria, it would have grown to $549,087 by 2016. Who would have thought in 1966 (and certainly in 2017) that tobacco, not computers, would win the future (at least in terms of returns).

Some of the other top-performing stocks over this period were also surprisingly non-innovative and low tech. For example, Coca Cola returned $34,403 and its cola rival Pepsico returned $21,084, better than any of the tech companies that would change the future.

Or in the shorter-term, let’s look at the summer of 2004 when two firms went public, Google and Domino’s Pizza. Many rational investors given the choice would probably assume that Google was the better investment. And they certainly did well over this period, returning 1,555% through January 14, 2017. But Domino’s delivered a cumulative 2,401% return.

What are some of the risks in investing in innovation?

Many times, innovative companies fall victim to second mover advantage as other firms build on and enhance the original technology. Think of how social media platforms like My Space were superseded by Facebook or smartphone makers like Blackberry were outmoded by Apple’s iPhone. It is hard to know whether a company will be a failed leader or a successful follower.

Also, the initial results of innovation can be hard to maintain. Think of once great firms such as Wang Computers or Nokia or Kodak (the inventor of the digital camera) that could not keep up and fell by the wayside. By market capitalization, Apple is the largest company in the world. Millions of people use and love their products. But will they still be a tech leader 10 years from now? 20?

In comparison to growth stocks, which are very often innovative, forward-looking companies with strong earnings growth (or potential growth), value stocks are usually associated with generally less-innovative corporations that have experienced slower earnings growth or sales, or have recently experienced business difficulties, causing their stock prices to fall. Academic research has shown, however, that value company stocks have greater expected return potential — and greater risk — than growth company stocks. Since 1927, U.S. Large Value stocks, as measured by the Fama/French US Large Value Index, have returned 10.51% vs 9.43% for U.S. Large Growth stocks, as measured by the Fama/French US Large Growth Index. This makes sense, since riskier companies must offer a higher potential return to attract investors.

The future may be uncertain, and the companies of tomorrow may not always be the best investments now. But the future, taken as a whole, may be the best investment many of us make.

If we are prepared to take a patient, long-term perspective and buy and hold securities from thousands of great companies around the world, we may benefit from two powerful forces:

1. Compounding, which allows your money to grow exponentially over time. If your portfolio grows an average of 6%, for example, it will double every 12 years. In 48 years, $100,000 growing at this rate becomes $1.6 million.

2. The dynamic potential of stock markets, fueled by human innovation, to create wealth over time.

We don’t know which firms will soar and which will fail, which will invent amazing new products and which will make money by doing what they have always done. But if we own many of them and invest for the future, chances are we will be rewarded over the long term.

None of these top seven stocks have much in common with each other — pharmaceuticals, real estate, computer chips, equipment rentals, on-demand movies and discount travel — and the top performing stock, ULTA Salon, is not some technological innovator, but a chain of salons/beauty stores best known for their discounts.

None of these results were predictable in advance. And even if you knew with absolute certainty that a specific policy or law would be enacted during the Trump administration, the impact on a particular stock price likely would be equally uncertain.

So what is an investor to do? Ignore the pundits, diversify broadly and globally, and embrace uncertainty and the potential it may offer to reward you over the long term for the risks it entails.