The News You Need To Know | January 2017

An unanticipated event.

Provided by Loring Ward

Without question the biggest story of the fourth quarter, in fact all of 2016, was the U.S. presidential election. Regardless of your political leaning, it is a fair bet that market performance during and after the election qualifies as what market analysts like to call “an unanticipated event.” In this fourth quarter briefing we will briefly examine how the presidential election seemed to reverse a slight decline of recent highs for the stock market (and also to accelerate declines in the bond market). Then, using events in this most recent quarter as a backdrop, we will take a much broader historical look at whether market reversals are predictable in and of themselves.

As the stock markets entered the fourth quarter of 2016, it seemed like the all-time high the U.S. markets reached in mid-August was starting to fade. Markets, as measured by the S&P 500 index, had pulled back about 2% – 3% from the high by the quarter’s start and seemed to be in a holding pattern. By the Friday before the election the markets were down more than 4% from their 2016 highs. But at the start of election week, things started to change. In fact, in the 38 trading days from election week until the start of 2017, the S&P 500 was up 8% and the Dow Jones Industrial Average was up 11%.

Even more amazing was the consistency of the strength — nearly 72% of those trading days were positive trading days, as compared to the 51% daily positive rate we observed in 2016 prior to the election. And to top it off, 17 times in that 38-day period the market broke through to all-new historic highs.

As for U.S. bond markets, one important event in Q4 was the post-election increase in short-term rates by the U.S. Federal Reserve. The Fed raised its target rate by 0.25% in mid-December, the second time in about a year, to a range of 0.50% to 0.75%. The rise in long-term U.S. interest rates (e.g. the Treasury 10-year rate) accelerated the upward trend that began in July 2016. During Q4, the 10-year Treasury rate rose 85 basis points, from 1.60% to 2.45%. The shorter, two-year Treasury rate rose 43 basis points, from 0.77% to 1.20% during Q4.

The reaction to the U.S. presidential election was interesting in some of the specialty areas of the stock market as well. U.S. large cap value, as measured by the Russell 1000 Value index, was up 11.2% after the election (vs. a rise of only 6.5% for U.S. large cap growth, as measured by the Russell 1000 Growth index,). Interestingly, U.S. small cap stocks, as measured by the Russell 2000 index, exploded, rising 18% in those 38 trading days.

Foreign stock markets did not seem to react as well to the U.S. election. Developed markets fell very slightly during Q4, while emerging markets were down about -4%, as measured by the MSCI Emerging Markets index. On the bright side, international value stocks rose almost 5%, as measured by the MSCI World ex USA Value index, in Q4. U.S. real estate markets, as measured by the Dow Jones US REIT index, fell about -2.5% in the quarter.

Can you sidestep a falling stock market?

All of this raises what we believe is a more interesting question: Can we somehow use a market decline as a way to sidestep losses? The 4% pullback from the August high lasted almost three months. Would it have been feasible to try to step to the side and avoid that loss? We certainly know after the fact that if we had stayed out of the market too long we might have missed some or all of the post-election market rebound.

So our in-depth topic for this quarter is to examine whether we can ever use information in the market to sidestep a market decline, but get back in time to capture any rebounds.

In last quarter’s briefing we determined that the stock market isn’t at any more risk of falling after reaching an all-time high than at any other time. But what about those “other times?” Is there anything we can identify in the market that might help us know when to get out of the way of a market that is at risk of falling further?

To answer this question, we looked at 66 years of prices for the S&P 500 index and identified every prolonged market drop the S&P 500 experienced during that period. We know that the market has always pulled out of these sustained drops eventually, but some of them can be painful, both as to how far the market falls and how long it stays low.

Some of the 500+ market drops we identified were over very quickly and didn’t fall very far before the market recovered. Other drops were very painful or took a very long time for the market to recover back to a profitable level. Is there any way to take advantage of these drops? Can we at least get out of the really deep or really long drops before they hurt our portfolios? Of course since the markets recovered from every drop we looked at, we would also have to know when to get back into the market so as to not miss the recovery.

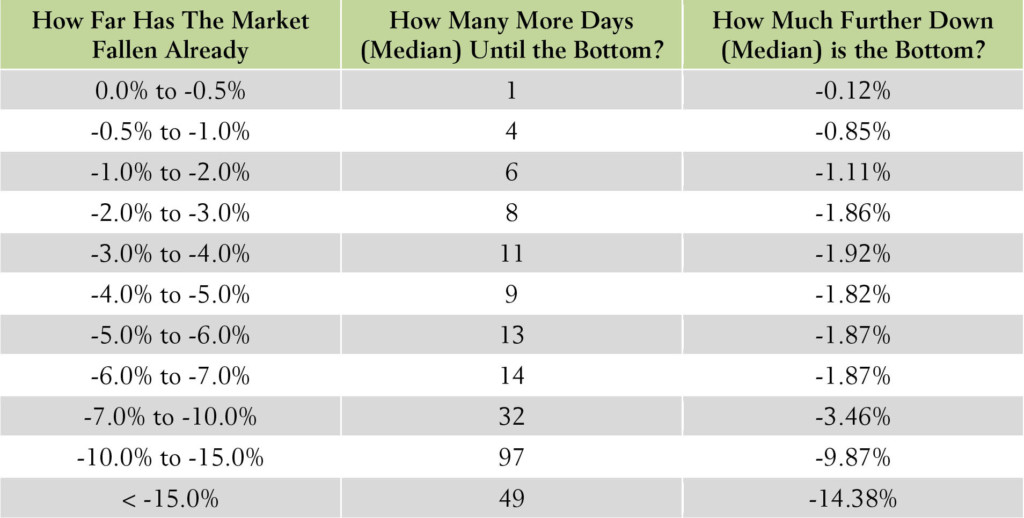

An examination of how much further and longer the market will fall if it has already fallen a certain amount

Source: S&P 500 Daily Closing Levels, LWI Through Calculations

To take a look at this idea we examined a really simple rule of thumb — does it help to get out of the stock market when it has already fallen by a certain amount? The table above shows the results of our trying to test this simple rule of thumb. If we get out when the market has fallen 4%, for example, and we stay out for a month or two, will we avoid some losses?

The table shows us that, generally speaking, it isn’t a good idea to try to get out of the market when it is falling. For example, if you get out when the market has already fallen 4% – 5%, the market will continue to drop, on average, another nine days before it hits the bottom and starts to go back up again. (In those nine days, it will fall, on average, another 1.82%.) If you get out earlier, before the market has fallen a lot, the market may begin its recovery while you are still invested only in cash. Once you get out of the market, it is difficult to time exactly when to get back in — many investors lose money by missing the market rebound.

The conclusion to draw from our analysis is that while market declines can sometimes feel painful, we believe it is a mistake to try to use any type of signal to help you get out of the way of a falling market. Markets are efficient, and our study is just further evidence that long-term investing, without panicking over the occasional market pullback, is a key to solid portfolio growth.